Exercise - Three Objects, Three Trees

(In a 2-day format, this could be assigned as homework).

The goal of this exercise is to solidify two major concepts:

- The Three Objects - the git data model

- The Three Trees - managing local changes

Work through this entire exercise, poking around in the project repo you started in Session 1. We'll have already touched on these concepts, but this exercise is designed to test and expand your understanding.

This should help you hit the ground running in Session Two.

Table of Contents

- Set up git Aliases - Command-line shortcuts for git

- Git versus Github - Which operations go with each?

- The Three Objects - Git's Data Model

- The Three Trees - Managing local changes

Review Basic Unix and Shell.

Set up git aliases

This activates cool bash shortcuts for working with git from the bash prompt.

$ cat bin/git-aliases.sh # See what's there

$ source bin/git-aliases.sh # Activate aliases in current shell

$ bin/append-aliases-to-profile.sh # So they'll be part of future shells.

$ adog # This should work now.

Git versus Github

The git client is a big bag of commands for implementing version control using a local content-addressable DB (aka a repository, or "repo"), as well as efficiently communicating with other, remote repos--a Distributed Version Control System, or DVCS. Git was written by Linus Torvalds in 2005 for version-controlling the Linux kernel.

In 2008, the social coding platform github.com came into existence, built around the git client.

When working with the git client and github.com, it's useful to keep in mind which operations/concepts belong to which tool.

| git | github.com |

|---|---|

| repo | repo |

| clone | fork |

| pull | pull request |

| commit, push, merge | org, team, collaborator, org owner |

The Git Data Model - The Three Objects

Exploring the git repo - SHAs and objects

The git database

The git DB is "a content-addressable filesystem". That is, objects are stored and retrieved using keys ("addresses") based on their content. These keys are referred to as "SHAs".

How is this done?

From your repo's root directory, take a look around using the following as a guide. NOTE: Your values for git SHA's will be different than what is shown here, since the contents of your objects are different.

$ git rev-parse HEAD

9cd690631f73c4a396e02348744a3a2379f737bc

$ ls .git/objects/9c # First two characters of HEAD's SHA...

d690631f73c4a396e02348744a3a2379f737bc

Where did the '9cd69...' string come from? It's the address of the latest commit, generated by running that content through a SHA-1 hashing algorithm.

How do we know it's a commit?

$ git cat-file -t 9cd69

commit

What's actually in the commit? Use "-p" instead of "-t" ...

$ git cat-file -p 9cd69

tree 07018552500e8ebd52c2011c51a9b21a01c11ce4

parent b1c24a12c733be55ab2512fc003a84405bf68126

author Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

committer Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

ignore _site directory

Note the format of the commit record, and its fields: tree, parent, author, committer. (And after a blank line, the comment).

Test your understanding: Are all SHA's commits? Are all commits SHA's? Describe the relationship between a SHA and a git repo object.

Exercise: Commit hi.txt through "normal git commands"

Create a hi.txt file with a line or two of content in it, and commit it into the repo, using the customary git add and git commit (or their equivalent aliases)

- What SHA corresponds to the commit?

- Can you find that SHA under .git/objects?

- Extra credit: Using

git cat-file -p, can you trace from the commit SHA, all the way to the blob SHA that contains the actual contents ofhi.txt? HINT: there is a 'tree' SHA between the 'commit' and the 'blob', which is revealed through judicious use ofgit cat-file -p. What is the SHA of that blob object? - How would you print the contents of your hi.txt file, using

git cat-file -p?

While we're here...What else can we see in .git?

$ cd .git

$ ls -l

$ file HEAD

HEAD: ASCII text

$ cat HEAD

ref: refs/heads/main

$ file refs/heads/main

refs/heads/main: ASCII text

$ cat !$ # BANG-dollar! bash shorthand for "last argument of previous command"

fc223df6e6f71a506f9bda0fac71b16041fd7004 # Your SHA will differ from this one (why?)

$ ls -l refs

$ ls -l refs/remotes

$ ls -l refs/remotes/origin

$ file refs/remotes/origin/main

$ cat !$

fc223df6e6f71a506f9bda0fac71b16041fd7004

So, how is HEAD stored in the git repo? How about local and remote branches?

The Three Git Objects - Commit, Tree, Blob

What kind of SHA is HEAD?

$ git cat-file -t HEAD

commit

Let's look at the origin/main commit (HEAD was the same as origin/main, until you committed hi.txt).

$ git cat-file -p origin/main

tree 07018552500e8ebd52c2011c51a9b21a01c11ce4

parent b1c24a12c733be55ab2512fc003a84405bf68126

author Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

committer Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

ignore _site directory

What kind of SHA is 07018?

$ git cat-file -t 07018

tree

What is in 07018? (Remember, your exact SHA, and its contents, will be different than this example)

$ git cat-file -p 9c94

100644 blob 1377554ebea6f98a2c748183bc5a96852af12ac2 .gitignore

100644 blob 5dbb683a366d3db08fa9adb8389759bc1a7151d1 about.html

040000 tree b926a635d3b58e146cbf9dad4593f75b6568e1c6 bin

100644 blob fa9e798a76c72b95ac7939eca39c432001eb637f faq.html

100644 blob 21fccfeade64cc2240f5395fa5949d612f5422f8 help.html

040000 tree abd4dc21a6bb32bc275bd095761187852a308393 images

100644 blob 16a46ac3537a1b56fd5dd8380df79463e3cea28a index.html

100644 blob 9103c17890d85e851d01765890932f9331102ba7 map.html

100644 blob e076b3f199fe75ee38d2e71981e0c266e189fb2b styles.css

What SHA contains the contents of the first entry in 9c94? What is that entry's name?

How do you tell whether it's a filename or a directory name? Hint: What kind of SHA is the first entry?

$ git cat-file -p 2d45b

__pycache__

venv

*.swp

*.pyc

*.sqlite3

_site

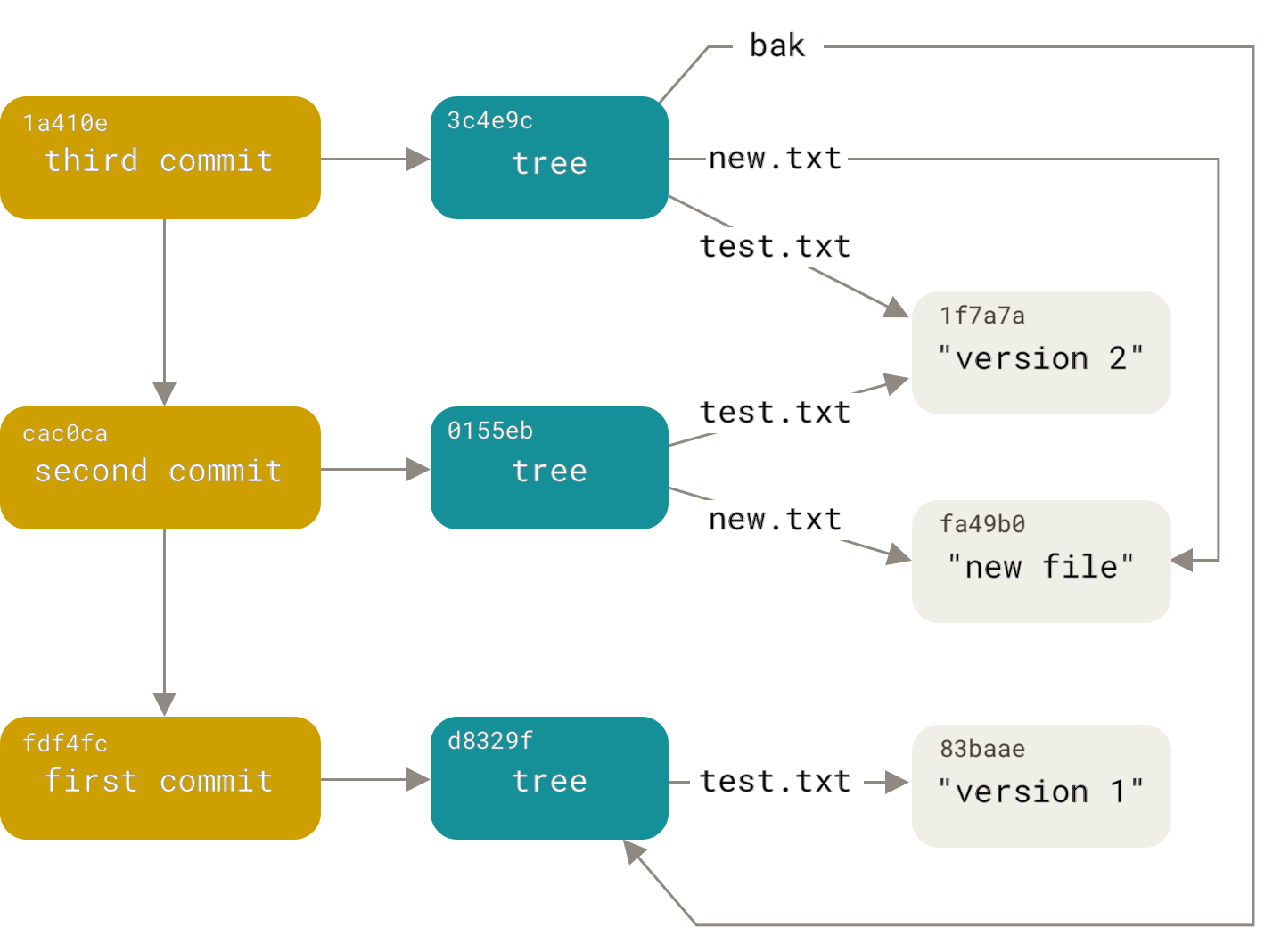

Consider this git object diagram, courtesy of git-scm.com:

What SHAs from your repo (whether commit, tree, or blob) would correspond to this diagram's latest commit?

So there they are: The Three Objects. commit, tree, and blob. Next up: How do they work in practice?

The Three Trees

HEAD, Index, and Working Tree

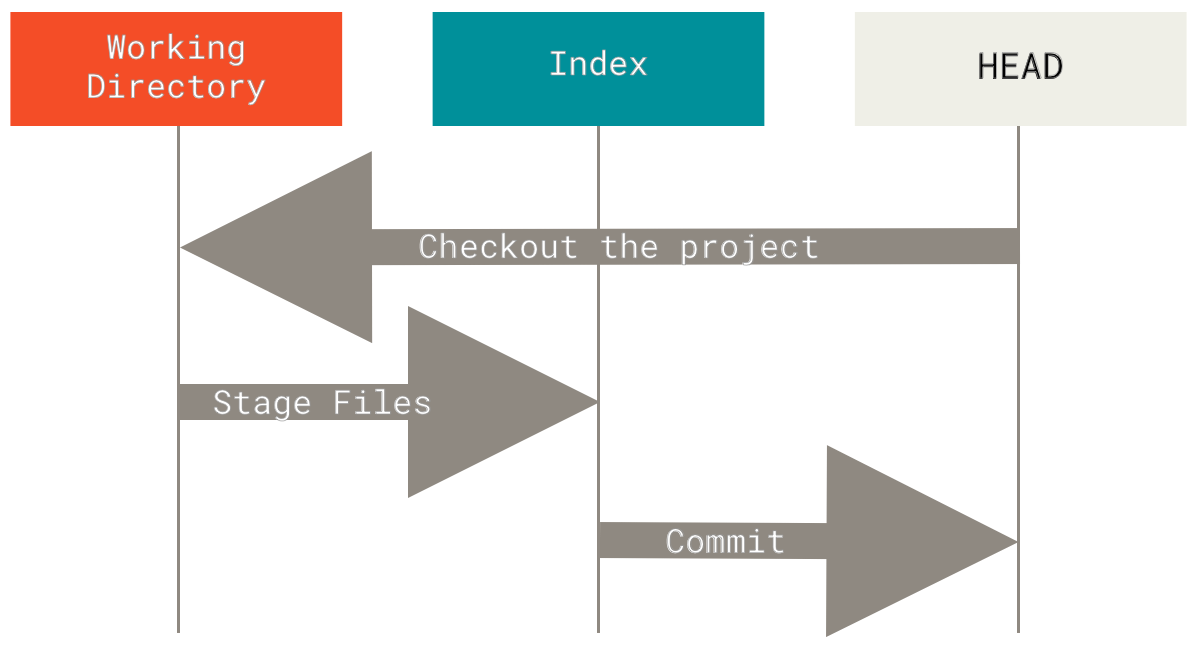

Git manages your local changes using three trees:

| Tree | Role |

|---|---|

| HEAD | The latest commit |

| Index | The commit-in-progress, aka "staging" |

| Working Tree | Your local filesystem (except for the .git directory itself |

On the 'green path' (that is, no mistakes or side journeys), changes start in the working tree and flow to the index via git add, and finally into the repo via git commit (i.e., the branch to which HEAD points moves to the next commit):

| Tree: | Working Tree | Index | HEAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operation: | 1. <make changes> | 2. git add (stage changes) | 3. git commit |

See also this workflow diagram from git-scm.com. Notice that a git checkout updates all three trees:

Sometimes it's necessary to move changes the other way. For instance, you may want to...

- Add a forgotten file,

- Change a commit message, or

- Revert a commit.

git reset: The command that can assist with all this and more. Why is it called "reset"? Possibly because it resets trees to a state that already exists in the repo. Unlike git add and git commit, which push new states INTO the repo, git reset propagates existing state the other way, OUT of the repo to HEAD, the index, and even the working tree.

| Tree | Role | git reset "hardness"needed to move the tree |

|---|---|---|

| HEAD | The latest commit | --soft |

| Index | The commit-in-progress | --mixed (also moves HEAD.) The default. |

| Working Tree | Your local filesystem | --hard (also moves HEAD and Index.) |

git reset needs to know two things:

- The "hardness"--that is, how many trees are to be reset, and

- Which commit SHA to (re)set the tree(s) to.

If you just type "git reset", the default hardness is "--mixed", and the default commit SHA is HEAD.

Putting It Together - Moving Objects Among Trees

Let's follow a single file through this workflow, starting with working-tree changes, which will move into the index, and then into a commit. Then, we'll revert it, tree by tree, all the way back using git reset.

1. Move a change forward through the trees

Make a change (which tree are you working in now, as you run the following commands?) such as adding a menu item link ...

$ code index.html # (or whatever file you may have in your working tree)

# Make a minor change to index.html in your editor, and save it. Then...

$ git status # or use the 'gs' alias

$ git diff # or use the 'gd' alias

Add to the index.

$ git add index.html # or use the 'ga' alias

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged # or use the 'gds' alias

Which tree (or trees) have the change now?

Commit it...

$ git rev-parse HEAD

$ git commit -m "Added a menu item link to index.html" # or use the 'gc' alias: gc -m "Added a..."

$ git status

Now which tree (or trees) have the change?

2. Move the same change backward through the trees

Recall that besides specifying "hardness", we need to tell git reset the commit-SHA to align with--that is, which SHA to reset to.

(What is the previous value of HEAD?)

$ git rev-parse HEAD

$ git reset

$ git rev-parse HEAD # What happened? Why?

$ git rev-parse HEAD^ # What does the caret (^) mean?*

$ git status

$ git reset --soft <previous-value-of-head>

$ git rev-parse HEAD

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

* To understand ^, ~, @{push}, and other revision notation, see Git Revisions.

What happened? What is git status telling you, and why?

What happened to the commit that we were on before doing a `git reset```? How might we get back to it?

Now the branch that HEAD points to has been "reset", back to where it was before we committed. Which tree has changed?

Let's change the next tree...

$ git reset # Same command, but now something happened. Why?

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

What changed this time?

Let's change the third tree...

$ git reset --hard

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

Test your understanding:

- What happened to each tree at each step?

- How is

git reset <paths>the opposite of `git add```? - When would each variation of

git resetcome in handy?

Another picture of how "git reset --soft/mixed/hard <ToThisCommit>" works

| "hardness" | Trees that are reset <ToThisCommit> | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Tree | Index | HEAD | |

| --soft | - | - | YES |

| --mixed | - | YES | YES |

| --hard | YES | YES | YES |