tags

Objects and Trees Handout

Agenda

- Intro & Setting Up Your Environment

- Basic Unix & Shell

- Git vs Github - Which commands go with each?

- Git Data Model - The Three Objects

- Managing Local Changes - The Three Trees

Intro & Setting up your environment

Start with the forked-and-cloned repo. See the Prework for fork & clone instructions.

Basic Unix & Shell

Review Basic Unix and Shell.

Unpack the git objects that Github.com has packed

$ ls .git/objects # Not much there

$ ls -1 .git/objects/pack # NOTE: -1, not -l

pack-cd347441ac47e2b50da184be5d8f0456b814e307.idx

pack-cd347441ac47e2b50da184be5d8f0456b814e307.pack

$ bin/unpack-objects.sh

$ ls .git/objects # That's more like it!

$ ls .git/objects/pack # Now the packfiles are gone.

$ ls .git/objects # Lots more there now!

Activate git aliases, append to profile

This will set you up with cool shortcuts to see what’s going on with your repo state.

$ cat bin/git-aliases.sh

$ ls -l bin/*.sh

$ source bin/git-aliases.sh # Activate aliases in current shell

$ bin/append-aliases-to-profile.sh # So they'll be part of future shells.

$ adog # This should work now.

Review the prework, if you haven’t yet

- Get the webapp running

- Explore the code

Git versus Github

The git client is a big bag of commands for implementing version control using a local content-addressable DB (aka a repository, or “repo”), as well as efficiently communicating with other, remote repos--a Distributed Version Control System, or DVCS. Git was written by Linus Torvalds in 2005 for version-controlling the Linux kernel.

In 2008, the social coding platform github.com came into existence, built around the git client.

When working with git and github, it’s useful to keep in mind which operations belong to which system. For instance…

| git | github |

|---|---|

| repo | repo |

| clone | fork |

| commit, push, merge |

|

| pull | pull request |

| org, team, collaborator, org owner |

Exploring the git repo - SHAs and objects

The git database

The git DB is “a content-addressable filesystem”. That is, objects are looked up (“addressed”) based on their content. How is this done?

$ git rev-parse HEAD

9cd690631f73c4a396e02348744a3a2379f737bc

$ ls .git/objects/9c

d690631f73c4a396e02348744a3a2379f737bc

Where did the ‘9cd69…’ string come from? It’s the address of the latest commit, generated by running that content through a SHA-1 hashing algorithm.

How do we know it’s a commit?

$ git cat-file -t 9cd69

commit

What’s actually in the commit? Use “-p” instead of “-t” …

$ git cat-file -p 9cd69

tree 07018552500e8ebd52c2011c51a9b21a01c11ce4

parent b1c24a12c733be55ab2512fc003a84405bf68126

author Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

committer Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

ignore _site directory

Note the format of the commit record, and its fields: tree, parent, author, committer. (And after a blank line, the comment).

Test your understanding: Describe the relationship between a SHA and a git repo object. Are all SHA’s commits? Are all commits SHA’s?

Exercise: Commit hi.txt through “normal git commands”

Create a hi.txt file with a line or two of content in it, and commit it into the repo, using the customary git add and git commit (or their equivalent aliases)

- What SHA corresponds to the commit?

- Can you find that SHA under .git/objects?

- Extra credit: Using

git cat-file -p, can you trace from the commit SHA, all the way to the blob SHA that contains the actual contents of `hi.txt? HINT: there is a 'tree' SHA between the 'commit' and the 'blob', which is revealed through judicious use ofgit cat-file -p```. What is the SHA of that blob object? - How would you print the contents of your hi.txt file, using

git cat-file -p``?

While we’re here…What else can we see in .git?

$ cd .git

$ ls -l

$ file HEAD

HEAD: ASCII text

$ cat HEAD

ref: refs/heads/master

$ file refs/heads/master

refs/heads/master: ASCII text

$ cat !$ # BANG-dolla! bash shorthand for "last argument of previous command"

fc223df6e6f71a506f9bda0fac71b16041fd7004 # Your SHA will be different (why?)

$ ls -l refs

$ ls -l refs/remotes

$ ls -l refs/remotes/origin

$ file refs/remotes/origin/master

$ cat !$

fc223df6e6f71a506f9bda0fac71b16041fd7004

So, how is HEAD stored in the git repo? How about local and remote branches?

The Three Git Objects - Commit, Tree, Blob

What kind of SHA is HEAD?

$ git cat-file -t HEAD

commit

Let’s look at the origin/master commit (HEAD was the same as origin/master, until you committed hi.txt).

$ git cat-file -p origin/master

tree 07018552500e8ebd52c2011c51a9b21a01c11ce4

parent b1c24a12c733be55ab2512fc003a84405bf68126

author Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

committer Chris Walquist <cwalquist@drw.com> 1615843154 -0500

ignore _site directory

What kind of SHA is 07018?

$ git cat-file -t 07018

tree

What is in 07018?

$ git cat-file -p 07018

100644 blob 2d45b22d4cbfebf78a5c78c46ecdc44fca2e1d27 .gitignore

100644 blob 60cfe42a4102d0ad6be5ec1373f3cec61a439b23 README.md

100644 blob 324e2e0cc5bfe49dd3faef7b674e7ba24c5347a7 app.py

040000 tree 577935a1899acf406349842178b4caf8ab171116 bin

100644 blob f9c1905abf276dce13ee3b883d50e699c450c728 config.py

100644 blob 719b71285df083da25fa967460beee0a520df64c config.yml.sample

040000 tree 6a51471d23a4c65df321b424ba35fb2651c95b9a config

040000 tree 3a8b3bfe5b18db9a7317480cf1ac77d217cc1e34 db

040000 tree 393a18221eb58a427601b4cd3b4cc7490ecc7037 lib

100644 blob 7bac10d65439b807b8cf852b2781d7782725fad3 main.py

040000 tree 8473c63a37cfec1c0458282195054aca4b7564a6 models

100644 blob 308747b19d7876166a1e8385652de498c4743599 requirements.txt

100644 blob 1f8bc52a33198cf0837159cec540611e65365cc1 views.py

What SHA contains the contents of the .gitignore file?

$ git cat-file -p 2d45b

__pycache__

venv

*.swp

*.pyc

*.sqlite3

_site

What kind of SHA is 2d45b?

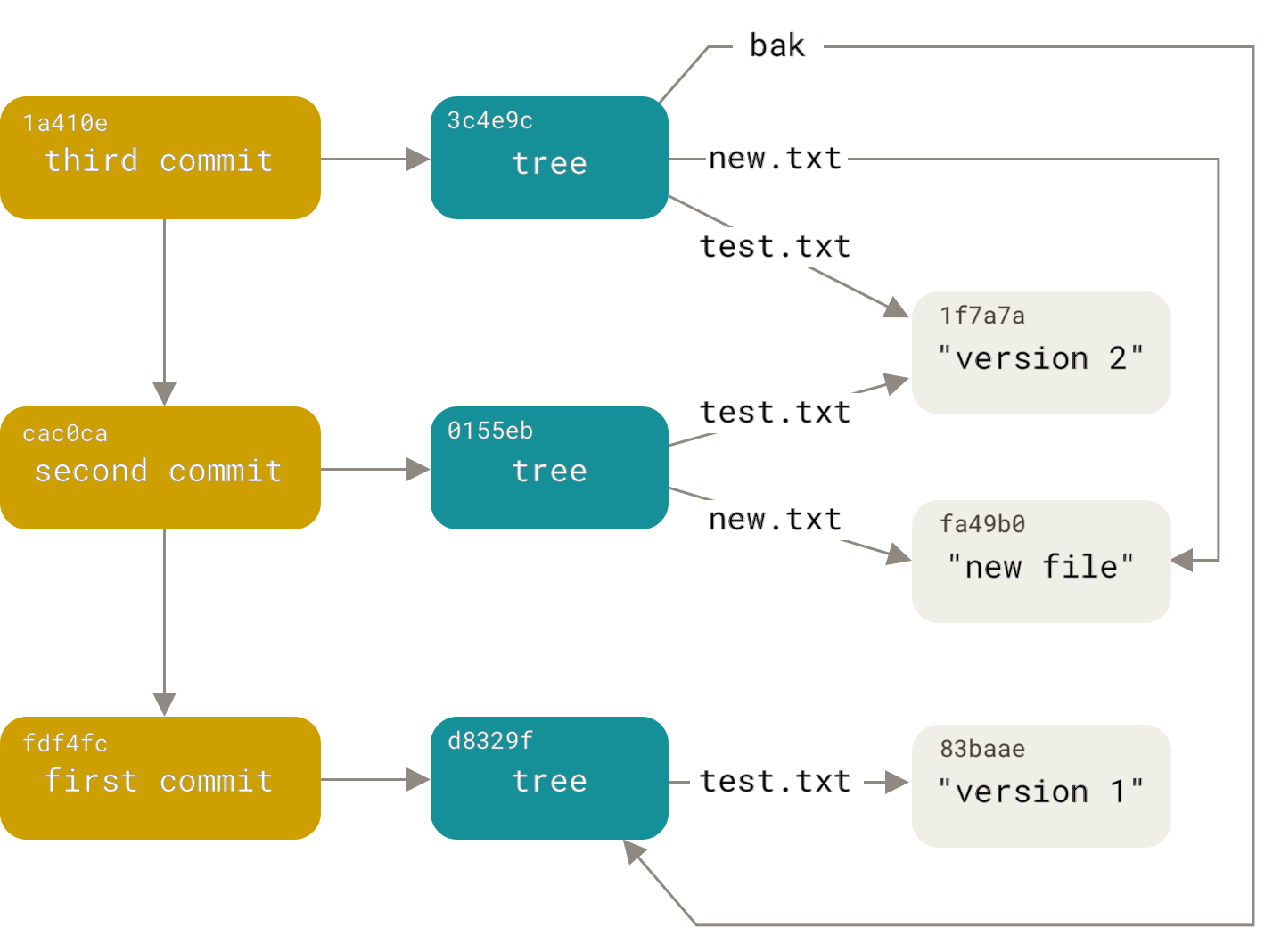

Consider this git object diagram, courtesy of git-scm.com:

What SHAs from your repo (whether commit, tree, or blob) would correspond to this diagram’s latest commit?

So there they are: The Three Objects. commit, tree, and blob. Next up: How do they work in practice?

The Three Trees - HEAD, Index, Workspace

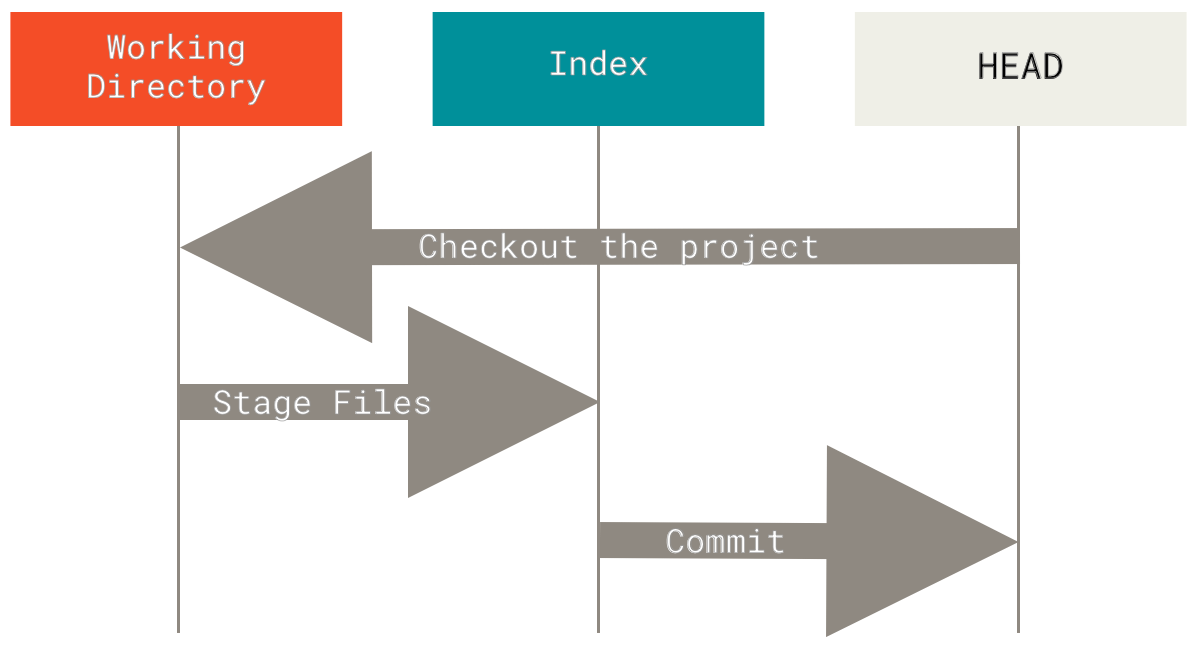

Git manages three trees in normal operation:

| Tree | Role |

|---|---|

| HEAD | The latest commit |

| Index | The commit-in-progress |

| Workspace | Your local filesystem |

On the ‘green path’ (that is, no mistakes or side journeys), changes start in the workspace and flow to the index via git add``, and finally into the repo via git commit (i.e., the branch to which HEAD points moves to the next commit):

| Affected tree: | Workspace | Index | HEAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operation: | <edit file> | git add |

git commit`` |

See also this workflow diagram, from git-scm.com:

Sometimes it’s necessary to move changes the other way–for instance, when you need to add a forgotten file, change a commit message, or revert a commit.

git reset: The command that can assist with all this and more. Why is it called “reset”? Possibly because it resets trees to a state that already exists in the repo. Unlike git add and git commit``, which push new states into the repo, git reset pulls existing state the other way, out of the repo, and into one or more of HEAD, the index, and even the workspace.

| Tree | Role | git reset “hardness”needed to move the tree |

|---|---|---|

| HEAD | The latest commit | --soft |

| Index | The commit-in-progress | --mixed (also moves HEAD.) The default. |

| Workspace | Your local filesystem | --hard (also moves HEAD and Index.) |

```git reset` needs to know two things:

- The “hardness”–that is, how many trees are to be reset, and

- Which commit SHA to (re)set the tree(s) to.

If you just type “git reset”, the default hardness is “--mixed”, and the default commit SHA is HEAD.

Putting It Together - Moving Objects Among Trees

Let’s follow a file through its lifecycle, starting with workspace changes, which will flow through the index, and into a commit. Then, we’ll revert it, tree by tree, all the way back using git reset``.

1. Move a change forward through the trees

Make a change (which tree are you working in now, as you run the following commands?) …

$ code views.py # (or use your preferred editor)

[Add a comment to the top--something prefixed with "#"--and save]

$ git status # or use the 'gs' alias

$ git diff # or use the 'gd' alias

Add to the index.

$ git add views.py # or 'ga' aFile.txt

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged # or use the 'gds' alias

Which tree (or trees) have the change now?

Commit it…

$ git rev-parse HEAD

$ git commit -m "Commented in views.py" # or use the 'gc' alias: gc -m "Commented..."

$ git status

Now which tree (or trees) have the change?

2. Move the same change backward through the trees

Recall that besides specifying “hardness”, we need to tell git reset the commit-SHA to align with–that is, which SHA to reset to.

(What is the previous value of HEAD?)

$ git rev-parse HEAD

$ git reset

$ git rev-parse HEAD # What happened? Why?

$ git rev-parse HEAD^ # What does the caret (^) mean?*

$ git status

$ git reset --soft <previous-value-of-head>

$ git rev-parse HEAD

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

* To understand ^, ~, @{push}, and other revision notation, see Git Revisions.

What happened? What is git status telling you, and why?

What happened to the commit that we were on before doing a git reset``? How might we get back to it?

Now the branch that HEAD points to has been “reset”, back to where it was before we committed. Which tree has changed?

Let’s change the next tree…

$ git reset # Same command, but now something happened. Why?

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

What changed this time?

Let’s change the third tree…

$ git reset --hard

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

Test your understanding:

- What happened to each tree at each step?

- How is

git reset <paths>the opposite ofgit add <paths>``? - When would each variation of

git resetcome in handy?

Another picture of how "git reset --soft/mixed/hard <ToThisCommit>" works

| "hardness" | Trees that are reset <ToThisCommit> | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Workspace | Index | HEAD | |

| --soft | - | - | YES |

| --mixed | - | YES | YES |

| --hard | YES | YES | YES |